Exploring Older PeoplesÃÆâÃâââ¬Ãââ⢠Perceptions of their Pathways through Healthcare: an Embedded MultiCase Study

Sue M Ashby, Roger Beech , Sue Read and Sian E Maslin-Prothero

Sue M Ashby1*, Roger Beech1, Sue Read1 and Sian E Maslin-Prothero1,2

1School of Nursing and Midwifery, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Clinical Education Centre, University Hospitals of North Midlands NHS Trust, Royal Stoke University Hospital, Keele University, Newcastle Road, Stoke-on-Trent, ST4 6QG, United Kingdom

2School of Nursing & Midwifery, University of Newcastle, New South Wales, Australia

- *Corresponding Author:

- Sue M Ashby

Professor in School of Nursing and Midwifery

Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Clinical Education Centre

University Hospitals of North Midlands NHS Trust

Royal Stoke University Hospital, Keele University

Newcastle Road, Stokeon- Trent, ST4 6QG, United Kingdom

Tel: +44 (0)1782 679550

E-mail: s.m.ashby@keele.ac.uk

Abstract

Background: A global trend of shifting healthcare to the community is taking place to meet the needs of an increasing ageing population. Resulting care pathways involve periods in different settings and care from different staff; diverting older people from hospital admission or facilitating early discharge. Person-centred care is advocated however this complexity draws attention to whether this can be achieved. This study explored older people’s perceptions of their entire experience of care in response to an acute crisis. The aim of this was to achieve an understanding of the impact this type of care has on older people.

Methods: A qualitative embedded multi-case study situated in one primary healthcare organisation and surrounding care providers in England; studying six people aged seventy five years and over. Application of a snowballing technique included carers and staff. Data collection included forty three semi-structured interviews and documents. Data was thematically analysed applying situational and dimensional analysis.

Findings: The themes of empowerment/disempowerment, involvement/marginalisation and safety/vulnerability are presented.

Conclusions: The complexity of achieving person-centred care pathways for older people is highlighted. The adoption of ways of working that applies identified supporting factors and recognises the tensions may help staff to engage in a more meaningful way with older people; maximising recovery and ability to cope with the future.

Keywords

Care pathways, Case study, Integrated care, Older people, Person-centred care, Shared decision-making

Introduction

It is widely acknowledged that the world’s population is ageing however a transformation of healthcare system is still required as the world come to terms with this change in society.[1-3] A global trend of shifting services to the community is taking place in efforts to manage cost and in recognition that older people benefit from care closer to home.[4,5] As a result differing approaches to integrated systems are taking place to address the known organisational barriers between primary and secondary care, health and social care and tertiary services. Sweden, acknowledged as a country with a high performing and innovative healthcare system, has adopted an integrated health and social care approach. Sweden’s healthcare system has pooled budgets and condition specific ‘chains of care’ adopting a multi-disciplinary team approach.[6] Placing a focus on integrated home and community care delivery for frail older people, Denmark has adopted preventative and self-care techniques; addressing gaps between nursing homes and home care services.[7] The Program of Research to Integrate the Services for the Maintenance of Autonomy (PRISMA) in Canada claims successful integrated service networks for older people with functional disabilities being cared for at home. This is attributable to the sharing of real-time information achieved by single assessment tools and access to online clinical information.[8] In the United Kingdom (UK) the term ‘whole systems working’ is adopted to embrace the philosophy of joined up pathways of care with the person being placed at the centre of care planning.[9] Throughout the UK, similar to other developed countries there is both a varying pace to the introduction of and differing approaches to integrated care for older people..[10] A pioneer of integrated care is Torbay and South Devon National Health Service (NHS) Foundation Trust. This Trust in 2015 brought together for the first time in England one single organisation responsible for acute and community healthcare alongside adult social care services..[11] However, little is known about how older people perceive these entire care pathways. This paper addresses this gap in knowledge by reporting findings from an exploration of older people’s perceptions of their experiences of care from crisis to rehabilitation in a number of settings. These settings are situated within the types of service developments that are taking place internationally.

The context for the study is healthcare services for older people in the UK. People over the age of 65 years constitute 18% of Accident and Emergency (A & E) attendances in the UK and are more likely to be admitted.[12] In this age group in the UK short hospital stays less than 1 day rose significantly faster (192%) than admissions longer than 2 days (20%).[13] These figures reflect situations where older people presenting with acute events now have the potential to enter faster paced often complex pathways of care: through a number of services, across organisations, interacting with a variety of staff. For example a more traditional route of care for a crisis such as an acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease may have typically included: admission to hospital via A & E or General Practitioner (GP), then a period of rehabilitation in a community hospital before returning to home. An older person may now access a variety of enhanced community services to prevent the necessity for an acute hospital stay. On the other hand if an acute hospital admission is appropriate, early discharge schemes facilitate shorter lengths of stay. People have the potential to be stepped down from acute care via a diverse number of care closer to home services including: hospital at home, intermediate care beds, reablement/enablement beds, intermediate or reablement/enablement care at home.[14] A person may be stepped up or down through a number of these services. This is dependent on need and skills provided within each service or area of care; as pathways emerge directing older people away from acute services and differing approaches to integrated care take place.

The aim of this research was to understand how older people experienced unplanned heath care following a health crisis; context was achieved by exploring perspectives from the older people, staff and where present informal carers. The older people’s care pathways were examined from presentation, treatment, rehabilitation and on-going care needs. This research took place in one primary care organisation and their partner health and social care providers in England. This paper presents the complex pathways experienced by the older people and the impact of identified supporting and detracting factors in relation to integrated care. The implications for staff and organisations supporting older people are also explored acknowledging the global debate continues on how to achieve integrated person-centred care for older people; in this challenging landscape of healthcare. Although the study took place during 2008, its findings are still relevant as the types of services and service developments encountered by the research participants are still taking place internationally. Indeed, as many developed nations are still seeking answers to achieving high quality, better co-ordinated, dignified and compassionate care [15], this research informs on-going concerns about how to achieve person-centred care of older people.[16] Person-centred care is defined as ‘a means of creating a collaborative relationship where people are supported to make informed decisions and manage their own health to achieve the outcomes they want’[p1].[17] Furthermore a methodological approach is illustrated which sensitively achieves recruitment and sustained participation of older people with a mean age of 89 over a period of four months. The methodological approach supports the following of individual pathways rather than a condition or system.

Methods

Study design

An embedded multi-case study design was applied in the context of health crisis and contemporary healthcare. Six embedded cases consisted of an older person situated in this dual context within the boundary of presentation of crisis to six to eight weeks post discharge from the intervening service(s). The application of case study method achieved analysis of the unpredictable complex situation of exploring the entirety of individual pathways through care. Case study is recognised as a distinctive strategy to apply when a how or why question is being asked about a contemporary set of events over which the researcher has little or no control.[18]

A convenience sample of six older people aged seventy five years and over were targeted as a group known as a high user of hospital services;[19] populated from an area proactively pursuing services for older people.[20]

Recruitment criteria also included: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or falls (presentations acknowledged as resulting in high hospital bed occupancy for this population and also conditions where care close to home options are relevant).[21] In addition the older people were identified as experiencing: an avoidable hospital admission (where if there were enhanced services available in the community the person’s presenting health crisis could be managed in their own home or a bed-based service in the community), a delayed discharge (where the person no longer requires care within an acute hospital setting but still requires a level of healthcare that is not available in the community), or an early discharge (a reduced length of hospital stay as a result of enhanced services being available in the community to provide a level of care which would otherwise have necessitated a longer stay). Assignment of patients to these categories was determined by using a modified Appropriateness Evaluation Protocol.[22]

Ethical issues

This study was part of a national study exploring the impact of governance on unplanned admissions of older people [23] with ethical approval obtained from the National Health Service (NHS) Research Ethics Committee (REC) number 07/H0305/60. The second phase of this project enabled a PhD student (SA), a registered nurse teacher with clinical experience of older people’s services, to conduct this reported research.

All potential participants were provided with a jargon free information sheet. The researcher (SA) gained written consent following an expression of interest to take part. Process consent was applied to ensure renewal throughout the research. Recognising the potential vulnerability of the older people, approval reflected that if the person lost capacity to consent during the research they would be withdrawn and identifiable data already collected with consent would be retained and used. To prevent distress, checks to identify the appropriateness of further contact were made with staff prior to arranging follow up interviews.

Data collection

Data collection included: semi-structured interviews (older people, their informal carers, staff providing care and the managers of the intervening services) and documentation (extracts from medical and nursing records). Interviews with six older people were aimed to be conducted at three points (at crisis, on hospital discharge (where relevant) and six to eight weeks post discharge). Interview questions explored peoples experiences of unplanned care e.g. Please could you tell me about [your admission/the intervention]. Additional interviews with informal carers and staff were obtained where possible at these points with agreement from the older people, applying a snowball sampling technique. Topic guides facilitated discussion having the flexibility to respond to individual circumstance. All interviews were digitally voice recorded over a 30 to 60 minute time period.

Data analysis and scientific rigour

Medical and nursing records were collated into tables providing underpinning information relating to the demographics of the older people and movement through services. The interviews were promptly reviewed and transcribed (SA). Follow up interview guides were informed by prior interviews applying a constant comparison technique to analysis. This in turn informed data collection at the later points.[24] Familiarisation enabled a more detailed coding achieved by: the process of identification of themes, developing categories, determining connections and refining categories in an inductive way, facilitated by the use of Nvivo 7™. The reliability of coding was checked by PhD supervisors (SMP/SR).[25] Saturation of the data was achieved when all lines of the interview transcripts had been coded, themes had been generated and repeatedly revisited. This ensured there were no omissions and rival explanations were made transparent and explored.[26] All data was contextualised by situational [27] and dimensional analysis.[28,29]

Findings

Firstly the research participants are presented identifying the interview schedule. This is followed by an illustration of the chronological pathways. A summary of the main themes is provided identified from analysis of these care situations: pathways of care, philosophy of care and interactions with staff. Factors influencing person-centred care are then presented. All participants have been assigned prefixes to preserve anonymity: the older people are identified with prefix P, staff providing frontline care is linked with prefix F, informal carers are linked with prefix C, Managers of services are identified with prefix M.

Research participants

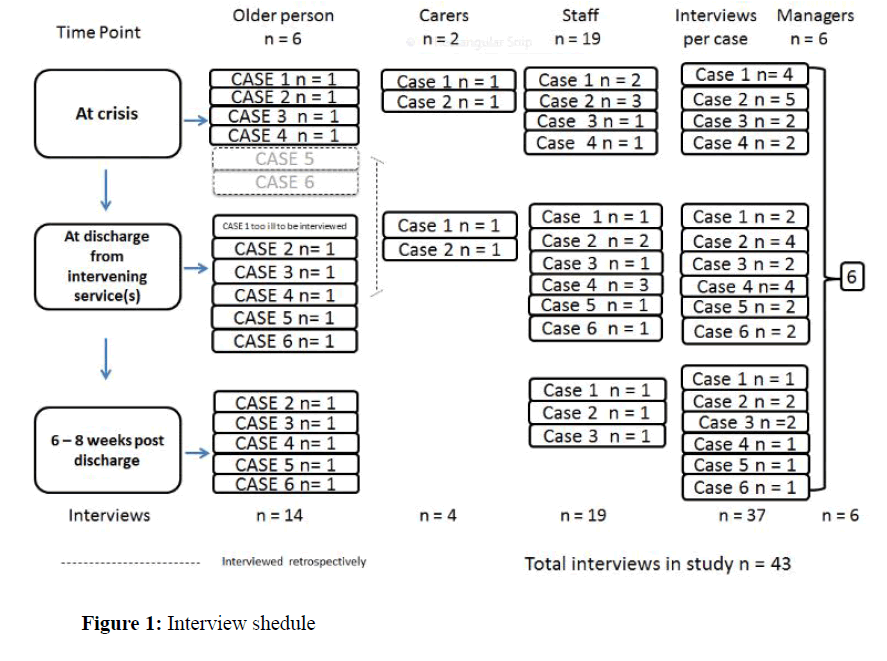

Four older people declined to take part in the study following initial expression of interest. The characteristics of the six females who consented are detailed in Table 1. Staff interviewed included: care assistants, nurses, therapists, social workers and managers from primary and secondary healthcare and statutory and private social care. In total 43 interviews were conducted Figure 1. One older person died before follow up and interviews for three other older people were condensed; covering experiences retrospectively. Four older people declined permission to contact their informal carers. The two informal carers who were interviewed identified themselves as main carers for their older relatives.

| Case study Participant |

Age | Ethnicity | Gender | Social circumstance | Presenting condition | Avoidable & prevented acute hospital admission | Avoidable & not prevented acute hospital admission | Delayed discharge from acute hospital | Early discharge/reduced length of stay from acute hospital |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| =P | 87 | White British | Female | Own property Bungalow Son main carer lives with participant | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | √ | √ | ||

| P1 | 86 | White British | Female | Own property Bungalow Lives alone Nephew main carer Maximum care package | Fall with fracture (Inside home) | √ | √ | ||

| P2 | 94 | White British | Female | Sheltered Private Accommodation | Fall with fracture (Outside home) | √ | |||

| P3 | 85 | White British | Female | Social housing Lives alone Independent | Fall with fracture (Inside home) | ||||

| P4 | 87 | White British | Female | Own property Lives alone Private cleaner | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | √ | (repeated admissions) | ||

| P5 | 93 | White British | Female | Own property Lives alone Independent | Fall with fracture (Inside home) | √ |

Table 1: Participant characteristics.

Pathways of care

The chronological context of each complex experience is illustrated in Table 2. The pathways revealed that knowledge of community services was advantageous as staff could proactively support timely transfers to appropriate areas of care. For example P6 was successfully navigated by her GP to a community rehabilitation bed which was also medically supported by her GP; illustrating how person-centred care was achieved by the collaborative relationship between P6, GP and rehabilitation staff. P6 not wanting to be admitted to an acute hospital gained timely access to an area of care that could meet presenting needs closer to home; facilitated by the relationship the GP had with the bed based community service. Person-centred care was not easy to achieve in other situations. Collaborative relationships became challenged and older people were distanced from involvement and making informed decisions. For example staff in acute hospitals and community rehabilitation areas spoke of the balance of monitoring the progress of older people in their care, re-assessing appropriate and timely transfers of care and matching need to the availability of resources:

| Case | Route | Sequence of health crisis management | Resulting situation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A+E | Acute Ward | Rehabilitation | Home | |||

| 1 | 999 | Diagnosed infected exacerbation COPD | Respiratory/ 40 day stay | No | 13 days | Participant died day 13 following discharge |

| 2 | 999 | Overnight stay A+E | No | Rehabilitation at home - Rapid Response Assessment | Admitted to Intermediate care unit Community Hospital (13 week stay) | |

| Diagnosed fractured humerus and pubic rami | Unable to cope | Resumed maximum care package at home | ||||

| Rapid Response assessment following day | ||||||

| Discharge home with intervening service | ||||||

| 3 | 999 | Diagnosed fracture | Developed pneumonia/ 8 week stay | Intermediate Care Unit Community Hospital/10 week stay | Home to warden controlled sheltered accommodation | Able to return to previous home circumstance with increase in care package |

| 4 | Diagnosed fracture and hypothermia | 3 bed moves | Social services rehabilitation bed | Home independent | Able to return to previous home circumstance | |

| 999 | (3 days at home on floor undiscovered) | 19 day stay | 30 day stay | |||

| 5 | GP | No | No | No | Home 3 days post discharge acute hospital | Emergency social services bed based admission |

| Unable to cope | Progressed to Long Term Care | |||||

| 6 | GP | A+E to access diagnostics – X-ray | No | None in interim period | Home 2 days awaiting Social Services rehabilitation bed | Admitted to Social Services Rehabilitation bed/(6 week stay) |

| Returned home with a care package | ||||||

Table 2: Chronological context of pathways.

Acute staff: ‘Sometimes, it’s waiting for the rehab beds to become available, sometimes there’s lots and sometimes you’re waiting a length of time and we are stretched’ [P4F1].

Community rehabilitation staff: ‘I’m sure we could have them sooner [patients from the acute hospital] because they could have been sat there for four or five weeks and not done anything at [acute hospital] and then we’ve got all the hard work to do when they come to us’ [P2F1].

Therapists were significant in the success of the older people’s pathways with home assessments being valued as risks were jointly identified and addressed tailored to individual need:

Older person: ‘And it was a wonderful experience [home assessment] and to have these two social workers with me was absolutely fantastic because they saw the drawbacks for me and it was done straightaway.’ [P3]

Social worker: ‘It seems to be now that the assessments are carried out on the ward which often doesn’t give a true picture of that person’s ability in their own home [P1F1].

However, the older people targeted for rehabilitation were marginalised from therapy input which hampered person-centred care:

Acute therapy staff: ‘… obviously our priorities lie with patients that are being discharged home, … if they live alone they are our priorities, whereas patients who are listed for rehab, as much as I’d like to get round and see all of them, sometimes it’s just not feasible …’ [P4F1]

Philosophy of care

This older person recognised ‘a doing for’ philosophy hindered her independence and timely return to their home:

‘I knew certain things I could do myself without any help and it wasn’t being taken into consideration’ [P3].

On the other hand staff reflected on how actions of colleagues could influence how older people responded to environments of care; a relative used the term ‘institutionalised’ [P2C1]. A rehabilitation staff member reinforced this opinion:

‘… quite often the patients have come from an acute hospital and have already got into that sick role … we spend the first week or so undoing what’s happened already’ [P3F1].

However rehabilitation was a valued opportunity [P2; P4; P6]. The significance of this is evident in this older person’s reflection:

‘I think the care I’ve had has been wonderful, I really speak highly of [rehabilitation unit]. I was all … well all my confidence had gone completely’ [P6].

The staff involved in this research identified with their experiences of trying to achieve person-centred care for the wider population of older people they came into contact with. Managers highlighted the pressure to manage resources and the efforts made to support older people: giving opportunity to discuss concerns and preferences, informing individualised care and time to make life changing decisions. For example this manager makes a reference to ‘valuable beds’ as they justify the allocation of this resource and how they achieved a more person-centred approach:

‘... He’s going to take up one of our valuable beds now … he and his family need that, transition. But I think everybody needs that time, unless it was on the cards before they came here [acute hospital]’ [M1].

Interactions with staff

Contact with a number and variety of staff was difficult for the older people as a lack of understanding of roles and for some a lack of understanding of how care was being managed was identified. For example when questioned about monitoring of their long term condition, older people advised that they did not have regular contact with their primary care professionals following their acute crisis:

‘… they gave me tablets and that was it’ [P4].

‘Doctor [name] didn’t see me after that, [discharge from rehabilitation] and they’ve never made any enquiries since I’ve been home, which I’m a bit cross about’ [P6].

These older people associated the doctor as the person who would monitor their situation; shared decision-making became compromised, as the opportunity to plan care with a variety of staff was not recognised. Compounding this was the issue of staff working in isolation, although working within a team providing care. This resulted in the older people being repeatedly asked for the same information as this rehabilitation team member comments:

‘But they [care plans] are still written by each profession separately. Although we do talk about it and liaise with each other, some of them overlap but the Physios will be working on one thing and the OTs might be working on another. So it is still quite disjointed’ [P3F1].

This was further challenged by incompatible Information Technology which resulted in staff having to search for information. This staff member indicates this was not an easy task; referring to having to ‘dig deep’ [P4F1]. Staff across organisations commented on organisational issues being the main reason for delays, highlighting the challenges of achieving timely shared decision making which compromised person-centred care.

Community rehabilitation staff: ‘I think the care path of the patient is not looked at holistically. You know, acute is acute, rehab is rehab and they don’t feel to be joined up' [P2F1].

Acute rehabilitation staff: ‘… the time taken to organise a discharge planning meeting, organise staff to be involved and family to come in, that may be another week down the line so during that time they’re taking up an acute bed while you’re waiting for the discharge planning meeting to be in place’ [P4F1].

The impact on older people

The identified supportive and detracting factors which influenced person-centred care in this research are summarised in Table 3.

| Transitions in: health, role, relationships, expectations and aspirations, environments influenced by health policy | |

|---|---|

| Supportive factors | Detracting factors |

| •involvement of the older person | •exclusion from decision making |

| •recognition of the ageing process | •lack of recognition of the progression of chronic disease management to end of life care |

| •managing co-morbidity | •lack of involvement in decisions in relation to end of life care |

| •focusing on ability | •lack of acknowledgement that choice may be limited due to availability of resources |

| •integrated care | •delivering contemporary care in designated areas also providing traditional services |

| •giving time to make decisions | •resources lacking in ability to support privacy and dignity |

| •informed choice | •balancing of older person and carer needs and choices |

| •establishing and prioritising care from the older person’s perspective | •striving for unrealistic goals |

| •flexibility in service design to meet the needs of older people | •striving to eliminate rather than minimise risk |

| •acknowledging the older person’s aims for their future | •gaps in care including lack of lower level preventative support |

| •knowledge of care closer to home services to support timely referral | •prioritising care from the perspective of service and organisations. |

| •establishing prior circumstance (medical, social, psychological) | •misunderstanding of care management by older people/carers |

| •accessibility to support and monitoring mechanisms in primary care | •lack or limited knowledge of contemporary healthcare and for older people subsequent expectations |

| •continuity of care by established formal carers | •focus by professionals on their specialist knowledge |

| •recognition of carer need and provision of appropriate support | •focus by professionals on the process of care |

| •older person’s awareness of carer’s needs | •poor communication across interfaces of care |

| •incompatible communication systems | |

| •duplication of assessment | |

| •lack of involvement of carers | |

| •restrictive service criteria | |

| •complex healthcare systems | |

| •exclusion from home assessment | |

| •delays in meeting care needs | |

Table 3: Factors influencing person-centred care.

The identified factors resulted in the older people being empowered or disempowered, involved or marginalised, feeling safe, or feeling vulnerable.

Empowerment/disempowerment

Empowerment was experienced when the older people were able to adapt to situations. This was achieved by being in a position to have an informed choice or at least an understanding of what care was available; being able to understand situations enabled the older people to cope. Coping was evidently linked to staff understanding how significant it was for the person to be in a position to manage their future. However, choice was at best limited to what resources were available at the time which in reality could result in no choice. Staff attention was drawn to balancing demand and meeting needs resulting in older people becoming compromised as they struggled to manage situations. For example P4 highlights how upsetting it was, not knowing when or where they were being transferred to, the relief when this was discovered and how she later reflected on the benefit of the rehabilitation she had experienced.

‘…my son rang up and I said “I feel a bit upset, I don’t know anything about [rehabilitation unit]”. So apparently he got onto the website or internet or something and got all the details and I said “oh it sounds great, you know I’m quite happy about going there”… But they don’t really give you any choice do they?’ [P4]

‘I don’t know what would have happened if I hadn’t gone to [rehabilitation unit], there’d have been no way I could have coped … what they’d do without those sort of places, I don’t know’ [P4].

The focus of being able to return to home environments was a definite coping mechanism for all the older people. This older person [P3] emphasised how this helped her to cope with situations she did not like:

‘ … you know with those six people in ward … eating and sleeping in one place [noise of disgust] I’ve got to the stage now when I know I’m going to be all right, I’m going home’ [P3].

Involvement/marginalisation

All the older people at some point in their pathway of care evidenced a lack of involvement in decision making. This lack of involvement marginalised people from expressing how they perceived their need and making informed choices about their future as this older person illustrates.

‘… And so against my will really I finally, I suppose they would say agreed, but there didn’t seem any option but to go home and it was then I found I wasn’t able to cope’ [P5].

The journey of P5 is given as an example to highlight how confusing pathways through care can become for the older person. P5’s choice on planning hospital discharge was residential rehabilitation however she did not understand that her condition was now palliative. This meant that she no longer met the criteria to access previously experienced rehabilitation services.

P5 was confused as she felt she had benefited from residential rehabilitation in the past so declined care at home. Links to palliative care at home were not established and P5 was discharged home with no support services. An emergency admission to a social services assessment bed three days post discharge from acute services was experienced. No one had discussed with P5 that her condition was palliative. During this assessment period decisions were made for P5 to remain in the nursing home where the assessment beds were situated. P5 remained confused about this process. She did not understand the difference between the assessment bed and the long stay bed that she had been moved to within the same nursing home. P5 reflected on making a hasty decision to enter long term care; in the subsequent weeks following admission to the nursing home. This position was reinforced by her specialist nurse:

‘I thought that maybe they would have referred her on to a rehab or [community hospital] or somewhere because she wasn’t feeling able to cope at home which is why she had to go in, in the first place because there wasn’t an intermediary bed available but I thought they might have found her one just to give her a bit of time but it didn’t happen’ [P5F1].

On the other hand when older people were viewed as being unrealistic about their limitations, it posed problems in determining future long term care as this relative recognises

‘… it’s not just about cognitive ability; it’s about hearts and minds on it you know’ [P2C1].

Staff had the dilemma of managing risk whilst respecting freedom of choice as rehabilitation staff illustrates:

‘... It’s mostly about, the choice from the patient, and if they’ve got the capacity to choose where they want to go, no matter whether the relatives or whatever have different opinions …’ [P4F3].

‘Every sort of experienced bone that I’ve got in my body is telling me, you know, there’s going to be another fall, another fracture …’ [P2F1].

Staff acknowledged the significance of informed decision making and managing risk however the older people displayed a lack of involvement at points in their pathways. This loss of meaning gave rise to uncertainty about their future.

Feeling safe/vulnerability

Feeling safe and being familiar with environments were identified as ways in which the older people maintained motivation and coped with recovery as these older people comment.

‘… my friends and whatnot say never be afraid, because if you go to the hospital for a long time they are very good at [community hospital] so when I knew I had got to come back again, well it didn’t worry me one bit’ [P2].

‘They were very, very kind. And I needed that help when I first went here [rehabilitation unit] … well all my confidence had gone completely’ [P6].

This security was also achieved when staff worked across the boundaries of community bed based services and the older person’s usual place of residence [P2: P4: P6]; as this older person acknowledges:

‘I was very pleased that [care worker] was still there, because she was the best before and she still is the best’ [P2].

Despite there being a diverse range of older people from very frail to actively independent each respective journey through healthcare illustrated vulnerability.

Becoming a burden to others was verbalized or displayed by actions by all the older people: for example this older person reflected on what she expressed as a hurried decision to go into long term care:

‘I just felt I was being a bit of an all-round nuisance …’ [P5]

P3 was so frightened of knocking an emergency pull cord on by mistake that she tied it up out of the way; defeating the whole object of it being there in the first place. Her thoughts about life reveal her search for meaning and purpose:

‘I question sometimes why at 95, I’m being kept on this earth… why am I being kept?’ [P3]

The older people in this research appeared to protect their informal carers with some not wanting them to be approached to take part (P3: P4: P5; P6); giving reasons related to taking up their time. However P2 was perceived by staff as not recognizing the strain they were putting on their relative and neighbours. The case manager recognised the relatives’ dilemma and commented that quality time with relatives and friends could be achieved if they were supported with some of their care:

‘Your friends would come back, you know the ones that you’ve worn out because the tasks that they were doing would be done by other people” but she’s not buying into it at all, complete denial. Her [relative], [name] is very, very worried about it because they feel much pressured by her.’ [P2F1]

There were clearly tensions in relation to person-centred care for P2 as the carer needs clashed with the choice of the older person to continue with care provided by her family and friends. This fear is clearly expressed by the relative:

‘I’m very aware of if a hospital feels that somebody’s at home to look after a patient they will put them in a wheelchair and leave them at the front door for somebody to pick them up and I wasn’t prepared to do that’ [P2C1].

Although the presence of informal carers was limited in this study their opinions gave strong messages about assumptions around roles and the fatigue of caring which illuminate vulnerability. The other informal carer in this study had great trust in staff as they were asked about their continuing caring role and discharge planning:

‘I’m not really competent to say. I mean she seemed all right, that last day I saw her in hospital … I presume they know their stuff, they see this all the time so they’d know when she was strong enough’ [P1C1].

However the hospital social worker’s opinion reveals another interpretation in relation to timely discharge:

‘Very frail but it was her decision that she wanted to go home and the support that was going in by the [relative] was judged at that time to be enough both by her and the [relative]’ [P1F1].

As this older person’s condition deteriorated (P1) person-centred care continued to diminish as it became apparent that neither the relative nor the social care provider were prepared for end of life care in the home. This was further complicated by the provision of agency nurses supporting the district nursing team at the time of this person’s death thirteen days following discharge.

Discussion

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has drawn attention to the issues which continue to relate to dignity and maintaining health and well-being in old age.[3] The WHO[3] identify that old age does not imply dependence and services should provide older person centred and integrated care with a focus on healthy ageing. Single service wide care plans are advocated to optimize the capacity of older people and enable choice.[3] This study has shown that as older people wait for assessment, treatment and safe environments there needs to be: a proactive approach to continually involve older people in decision making . There also needs to be a continuous focus on maximising and at least maintaining functionality. Countries continue to drive forward the philosophy of informed choice, shared decision-making and tailored care situated in integrated systems trying to achieve person-centred care.[17,30,31] However there is a continued acknowledgement of the fragmentation of healthcare services.[32] There is a requirement to shift the focus of complex chronic conditions from a purely clinical focus to enabling people to maintain independent at home with quality of life. [33-35]

This study has provided insight into the impact health care systems have in fostering dependency as older people present with unplanned care and become emerged in systems Examples of fragmentation are illustrated in this study and disjointed approaches to differing pathways of care and discharge planning. Implementation of person-centred care requires an alignment of organisational and professional philosophies to what is valued by the population; being sensitive to local need whilst also striving to achieve consistency.[36] Co-production is recognised as a way forward where the public, patients, providers and commissioners of services work together; ultimately to determine what matters to people and how this can be realised.[36] What matters has been reported in this study from the perspective of older people and staff offering insight into what still ‘needs to be done’ and ‘how people need to work differently’[p9] [36], as countries attempt to respond to the call to action by the WHO.[16]

The research targeted older people over the age of seventy five however achieved a population from the ‘oldest old’ (people eighty five years and over); a group where little is known about their perspectives of care;[37] with challenges acknowledged in recruitment and sustainment of participation of frail older people in research studies.[38] The research was achieved by a design which was able to access and keep pace with the older people as they moved through individual pathways of care and analysis which supported the contextualisation of data from these diverse pathways.

The voice of the older people in this research drew attention to the importance of making interactions with contemporary healthcare as manageable as possible for people to cope. The older people had more positive experiences when communication was orientated to their circumstances and level of understanding. This was accomplished at points rather than throughout journeys of care. P2, P3, P4 and P6 were empowered by being familiar with their initial discharge destinations. However when this changed for P4 to an unfamiliar destination of a local authority rehabilitation centre they quickly became disempowered and vulnerable. P1 had little communication as decisions were directed towards their son by staff; indicating disempowerment, marginalisation and vulnerability. P5 could not understand why they had been declined rehabilitation and quickly became disempowered, marginalised and vulnerable as they entered long term care and their status of palliative care was determined. As the shift to community services took place the process of reconfiguration was impacting on the older people as they waited for care closer to home. A lack of understanding of delays in care and a loss of focus on individual situations placed people in vulnerable positions minimising opportunity to achieve their full potential and maintain motivation towards active rehabilitation. It is recognised that well-being in old age is based on experiences of meaning and purpose in life.[39] Foss and Hofoss [40] debate the influencing factors in participation with decision making stating that amongst the oldest of individuals staff need to actively seek out participation and not make assumptions. For example in this study it appears many assumptions were made about the home circumstance of P1 and P4 which resulted in missed opportunities to receive more support with end of life care.

Information was not always complete for the older people due to a lack of openness or professional difficulties in keeping pace with an understanding of what services were available. A review by Maslin-Prothero and Bennion [41] identified the benefits of integrated working acknowledging that person-centred care was enhanced when staff worked across organisational boundaries. This was identified in this research: for example P6, whose GP also provided medical cover for a rehabilitation centre. However proactive approaches still experienced problems with the lack of compatible and ‘realtime’ information technology to support timely communication across the interfaces of care. For example if the specialist nurse working across primary and secondary care supporting P5 had been aware of discharge planning arrangements they may have achieved more time for the older person to understand their position and prepare psychologically for palliative care. P6 was empowered by knowledgeable staff placing them in a position to negotiate realistic choices surrounding place of care. This fostered coping abilities as the older people then managed situations alleviating anxiety and fear for their future. Where meaningful dialogue was achieved the older people had control and made informed decisions. For P2 this was supported by the presence of familiar support, as they expressed relief and established trust in known domiciliary carers and the community hospital. The older people needed to make sense of situations however there was uncertainty in their care pathways. Tensions were present between the ageing process, the progression of chronic disease management to palliative care and rehabilitation; reflecting the concerns of Canning [42] in that the transitions are acknowledged as problematic with non-malignant conditions. This may have been avoided if the focus had been on how individual need was changing in relation to progressive conditions as debated by Pinnock et al.[43] A dominant factor was the lack of involvement of the older people in the preparation for transfers of care, further hindered by periods of lost or no rehabilitation time; all contributory factors to a loss of power to plan futures also acknowledged by Goodrich and Cornwell [44] who advocated the need to see the person in the patient. The loss of focus on ability fostered a lack of confidence and well-being which gave rise to anxiety and fear for all of the older people in this research.

Staff with a raised awareness of the person as an individual was equipped to facilitate meaningful involvement of older people in care planning and decision making; resulting in informed choice. This awareness is debated by Foss and Hoss [40] and Read and Maslin- Prothero [45] who draws attention to the impact of meaningful involvement and engagement. This level of awareness supports a shift in the focus of care to working with risk rather than avoiding it; seeking out strategies to support older people with choice. A fear of losing control prevents older people from seeking advice in a timely way; the problem then has the potential to escalate.[46] An example of this was home assessments which were valued by the older people and staff; reducing inappropriate referrals and supporting individuals in recognising their abilities. However the staff in this research acknowledged that criteria and organisational need often marginalised older people they identified as benefiting from home assessments. Older people waited in these situations as others were prioritised. The damage of being labelled as a delayed discharge was raised by Kydd [47] who highlighted the feelings of stress and anxiety felt by older people in these circumstances.

Contemporary healthcare places demands on older people to actively engage.[45] This research has highlighted the significance of person-centred care achieved by meaningful communication accomplishing collaborative relationships between staff and older people. The older people expressed a need to be involved in decisions. If this was achieved they were better placed to negotiate realistic choices which made situations more manageable. Where staff had a raised awareness of the individual circumstance of the older person throughout their respective pathways, they were able to engage in more meaningful conversations. This was successful where dialogue was steered towards the identified factors which enabled older people to adapt and cope with situations. Staff who have an awareness of how older people perceive their care have the opportunity to take person-centeredness to a higher level of interpretation. This interpretation moves beyond the confines of systems and processes to a focus on collaboration; re-focussing the skills of the staff to the needs of the person regardless of place or time of care.[48] This research has demonstrated that older people in vulnerable situations can be sensitively involved to inform healthcare provision and could prove to be valuable members within co-production strategies.

Limitations

The limited informal carer interviews are cautiously reported, however their presence influenced pathways determined by older people and staff where interviews were not achieved. All the older people who took part in this research were White British. Data from the latest available census indicated that ninety six per cent of the primary care trust population in which this study took place were of this ethnic origin.49 Whilst ethnicity is acknowledged as significant the opportunity to recruit to this study population was limited considering the time span of the study. All of the older people within this research were female despite efforts to recruit males. Although this research was limited to older people presenting with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and falls, the significance of these conditions is emphasised as the trend of high interaction with healthcare services continues.[50,51] This research took place in the UK in 2008 however global reports continue to raise the same concerns about person-centred care for older people. As an acknowledged under reported population38 the findings of this study are considered insightful in these circumstance as they reveal the older persons perspective in an arena where more understanding is advocated to be sought.[36]

Conclusion

This research has highlighted the complexities of meeting the individual needs of the oldest old and the implications for effective communication throughout the entirety of healthcare interventions to achieve person-centred pathways. It is evident that the changes in healthcare across the world are impacting on communication at organisational, professional and service user level as organisations reconfigure and the shift to community care takes place. The efforts made to meet the needs of the older people by staff within this research have been explored acknowledging how older people are: empowered/disempowered, involved/marginalised, feel safe/feel vulnerable. An understanding of contemporary pathways from the perspective of older people has been identified. A model of communication that applies the identified enabling factors of: proactive engagement with older people, shared decision making, informed choice, continuity and integrated care and recognises the tensions between: organisations, professionals and the needs of the individual may help staff to engage in a more meaningful way with older people. This understanding may help organisations to reshape services and support staff to adapt approaches to care in a co-produced way. This approach maintains a focus on the person; sustaining person-centred care throughout intervention and on-going care needs. Steps to ensure the older person has manageability and meaningfulness embedded within their experience, by a more formalised approach, may improve the older person’s ability to cope. Empowering individuals at a time when active involvement in care is crucial to support recovery, future life choices and expectations. The sensitive inclusion of older people at a recognised time of vulnerability was achieved throughout this research; reaffirming both the importance of older people being involved in research to inform person-centred care and how this can be achieved.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by a phase within a national study funded by the United Kingdom National Institute Health Research Service Delivery Organisation Programme (project number 08/1618/136). The views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, National Institute Health Research Service Delivery Organisation programme or the United Kingdom Department of Health. Acknowledgement is extended to Martin Knapp the principal investigator for supporting this research and Angela Dickinson and Cate Henderson as co-researchers for their intellectual discussion throughout the phases of the national project.

References

- United Nations Populations Fund and Help Age International Ageing in the Twenty-First Century: A Celebration and A Challenge. New York and London: UNFPA and Help Age International 2012.

- Ashby S., Beech R. Addressing the Healthcare Needs of an Ageing Population: The Need for an Integrated Solution. International Journal of Collaborative Research on Internal Medicine & Public Health 2016; 8: 268-272.

- World Health Organisation. World Report on Ageing and Health World Health Organisation 2015.

- CBI The right care in the right place delivering care closer to home. CBI 2012.

- Royal College of Nursing Moving care to the community; an international perspective. RCN Policy and International Department Policy briefing 12/13. Updated December 2014.

- Anell A., Glennard AH., Merkur S. Sweden: Health system review. Health systems in transition 2012; 14: 1-159.

- Schulz E The Long-Term Care System for the Elderly in Denmark 2010.

- MacAdam M., MacKenzie S. System Integration in Quebec: The Prisma Project. Health Policy Monitor 2008. Naylor N., Imison C., Addicott R., Buck D., Goodwin N et al. Transforming our health care system. London: The King’s Fund 2015.

- Naylor N., Imison C., Addicott R., Buck D., Goodwin N et al. The King’s Fund 2015.

- Imison C., Poteliakhoff E., Thompson J. Older people and emergency bed use. Exploring variation. London: The King’s Fund 2012.

- South Devon Healthcare NHS Trust. Torbay Hospital News Autumn 2015.

- Wittenbery R., Sharpin L., McCormick B., Hurst J. Understanding emergency hospital admissions of older people. Oxford: Centre for Health Service Economics &Organisation 2014.

- National Health Service Benchmarking Network National Audit of Intermediate Care Summary Report. Assessing progress in services for older people aimed at maximising independence and reducing use of hospitals. NHS Benchmarking Network Document reference: NAIC 2015.

- Bluestone K., Escribano J., Horsted K., Mikkonen-Jeanneret E., Rossal P et al. (Eds) Facing the facts: The truth about ageing and development. Age International: London.

- Goodwin N., Smith J., Davies A., Perry C., Rosen R et al. A Report to the Department of Health and the NHS Future Forum. Integrated care for patients and populations: Improved outcomes by working together. London: The King’s Fund 2012.

- World Health Organisation Number of people over 60 years set to double by 2015; major societal changes required 2015.

- The Health Foundation. Person-centred care resource centre. The Health Foundation 2013.

- Yin RK. Case Study Research: Design and Methods 4th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications 2009.

- Department of Health. Our NHS Our future: NHS next stage review - interim report. London: Department of Health 2007.

- Leadbetter C. Beyond excellence. London: Improvement and Development Agency 2003.

- Department of Health. Urgent Care Pathways for Older People with Complex Needs Best Practice Guidance. London: Department of Health 2007.

- Bristow A., Hudson M., Beech R. Analysing Acute Inpatient Services: The Development and Application of Utilisation Review Tools. Report prepared for the NHS Executive South Thames. London: NHS Executive South East Thames 1997.

- Henderson C., Sheaff R., Dickinson A., Beech R., Wistow G, et al. Unplanned admissions of older people: exploring the issues. Final report. National Institute Health Research Service Delivery and Organisationprogramme; 2011.

- Savin-Baden M., Howell Major C. Qualitative Research. The essential guide to theory and practice. London: Routledge 2013.

- Mays N., Pope C. Rigour and Qualitative Research. British Medical Journal 1995; 311: 109-112.

- Cutcliffe J R., McKenna H P. When do we know that we know? Considering the truth of research findings and the craft of qualitative research. Int J Nurs Stu 2002; 39: 612-618.

- Clarke A E. Situational Analysis Grounded Theory After the Postmodern Turn. London: Sage 2005.

- Kools S., McCarthy M., Durham R., Robrech L. Dimensional Analysis: Broadening the Conception of Grounded Theory. Qual Health Res 1996; 6:3 312-330.

- Schatzman L., Kools S, McCarthy M, Durham R, Robrecht L Dimensional analysis: Notes on an alternative approach to the grounding theory in qualitative research. Qual Health Res 1996; 6: 312-330.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Patient experience in adult NHS Services Quality Standard 15. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2012.

- CoulouridesKogan A., Wilber K., Mosqueda L. Person-Centered Care for Older Adults with Chronic Conditions and Functional Impairment: A Systematic Literature Review. J Am GeriatSoc 2016; 64:1-246.

- Paparella G. Person-centred care in Europe: a cross-country comparison of health system performance, strategies and structures Policy briefing February 2016. England: Picker Institute Europe 2016.

- Watson J. Integrating health and social care from an international perspective. London: The International Longevity Centre 2012.

- Goodwin N., Sonola L., Thiel V., Kodner D L. Co-ordinated care for people with complex chronic conditions Key lessons and markers for success. London: The King’s Fund 2013.

- Royal College of General Practitioners An Inquiry into Patient Centred Care in the 21st Century Implications for General Practice and Primary Care. London: Royal College of General Practitioners 2014.

- The Health Foundation. Realising the Value Ten key actions to put people and communities at the heart of health and wellbeing. The Health Foundation and NHS England 2016.

- Karlsson S., Edberg A., Hallberg I. Professional’s and older person’s assessments of functional ability, health complaints and received care and service. A descriptive study. Int J Nurs Stu 2010; 47: 1217-1227.

- Baillie L., Gallini A., Corser R., Elworthy G., Scotcher A et al. Care transitions for frail, older people from acute hospital wards within an integrated healthcare system in England: a qualitative case study. Int J Integr Care 2014.

- Moore S., Metcalf B., Schow E. The Quest for Meaning in Aging. Geriatric Nursing 2006; 27: 293-299.

- Foss C., Hofoss D. Elderly persons’ experiences of participation in hospital discharge process. Patient Education and Counselling 2011; 85: 68-73.

- Maslin-Prothero S, Bennion A Integrated team working: a literature review. Int J Integr Care 2010; 10: 2

- Canning D., Margereson C., Trenoweth S. Chapter 22 In, (Ed) Developing holistic care for long term conditions. Oxon: Routledge 2010; 345-364.

- Pinnock H., Kendall M., Murray S A., Worth A., Levack P et al. Living and dying with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: multi-perspective longitudinal qualitative study. Br Med J 2011; 342.

- Goodrich J., Cornwell J. Seeing the person in the patient. The point of care review paper. London: The King’s Fund 2008.

- Read S., Maslin-Prothero S. The Involvement of Users and Carers in Health and Social Research: The Realities of Inclusion and Engagement. Qualitative Health Research 2011; 704-713.

- Richardson S., Casey M., Hider P. Following the patient journey: Older persons' experiences of emergency departments and discharge. Accident Emergency Nursing 2007; 15: 134-140.

- Kydd A. The patient experience of being a delayed discharge. J Nursing Manag 2008; 16: 121-126.

- Masterson A., Maslin-Prothero S E., Ashby S M. Using interprofessional learning to support intermediate care. Nursing Older People 2013; 25: 20-24.

- Office National Statistics. Office for National Statistics Census 2001 Population 2001; 2004.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Older patients at high risk of hospital falls. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2013.

- Tian Y., Dixon A., Gao H. Emergency hospital admissions for ambulatory care-sensitive conditions: identifying the potential reductions. London: The King’s Fund 2012.

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences